“That Game is Broken”

The other day I came across a post in which a tabletop RPG beginner was seriously stressed out about finding the right game. He had obviously read more than a few “this game is broken” comments and didn’t want to accidentally pick a “broken” game when introducing the concept of tabletop roleplaying to some classmates. His concern highlights a problem that pervades online discussion of tabletop RPGs, which is that we tend to confuse our quest for the ever-elusive “perfect” game with how people actually play games in the wild.

How Do We Choose?

If you’ve been playing tabletop RPGs for any length of time you likely have fond memories of your first gaming experience, because the fun of that first exposure is what you drew you into the hobby. For me that was playing a first edition D&D human fighter. I will always recall the thrill of discovery I felt as I embarked on my first tabletop roleplaying adventure.

Looking at the AD&D mechanics we played through the early 80s, it’s clear that they were unbalanced and unnecessarily complex. But the fact that we wound up leaving D&D for other games doesn’t at all detract from the fun we had with it. It was more than good enough as a point of entry into the hobby.

Had there been online forums at the time, I might have been paralyzed with indecision when offered the opportunity to play AD&D. I can picture myself wondering, “Should I suggest we play Tunnels & Trolls instead? What about Chivalry & Sorcery? Or RuneQuest? People are saying AD&D is broken because of THAC0 and because of how STR over 18 works, and because of Psionics.” That’s the environment we’re in now — a game’s faults are often presented as dealbreakers. It’s no wonder newcomers feel so much trepidation when selecting a game.

In practice I think we choose games because of what we like about them, and we put up with the aspects we dislike. In other words, I don’t look at a game and say, “Ah, this game isn’t obviously broken. Now I’ll see if it has interesting mechanics and an enticing setting.” Every game has core mechanical and setting elements that will either draw me in or not. If they draw me in and overall those elements are implemented in a way that reinforces my initial attraction, I’m likely to stick with the game. Especially if my friends at the table are similarly inclined. After all, tabletop roleplaying is a social endeavor that requires consensus.

How Do We Adapt?

Here are some examples of adaptation to imperfect games, from my own gaming history:

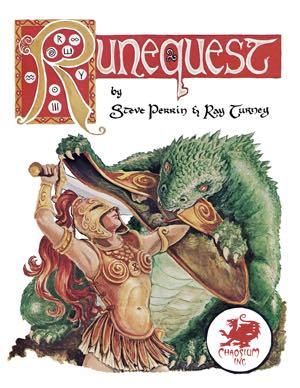

RuneQuest 2ed

I ran two lengthy RuneQuest campaigns. I was drawn into the system because of the d100 skills-driven task resolution, hit points by location, and the skill improvement mechanics. The Glorantha setting enticed me because it felt complex and deep, and magic truly infused everything in the world in an organic way.

It was a marvelous game, but imperfect. Some might even say it was “broken” in that beginning characters were quite weak. Combine that with a deadly combat system and you have a recipe for early character death. But we wanted to play in the amazing world of Glorantha. So we adjusted the play style we’d developed through years of D&D. I created adventures designed with the weaknesses of new characters in mind, and the players learned to only fight when necessary. We played an awful lot of this imperfect game, and loved it.

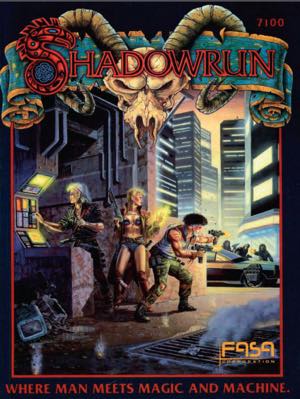

Shadowrun 1e & 2e

I ran one very long Shadowrun campaign that ended with the player characters as serious big shots, able to manipulate politics across the west coast of North America. We first picked up Shadowrun because cyberpunk was huge in the early 80s, and the idea of mixing magic and technology was too cool to ignore. The game was also built around running covert ops for megacorps, which provided a solid campaign scaffolding. We wound up taking the campaign in another direction, as the PCs became Metahuman rights insurgents. But that scaffolding made it easy to get the campaign rolling.

Shadowrun’s d6 dice pool system was complex. We had to make cheat sheets to help streamline play. And there were “broken” elements, like the power of certain weapons and cybernetics and the difficulty in running physical events alongside Matrix events. Again, none of this really broke the game. We loved the setting and the stories we were telling, so we figured out ways around the game’s rougher edges. Some gear became very difficult to obtain, and made you a target if you used it in an obvious way. We streamlined the Matrix rules, came up with simple mechanisms for coordinating between physical world and Matrix events, and played the game in a way that worked for us.

How Do We Talk About It?

It’s obvious that a good many “broken” games are being played and enjoyed by many players. Fifth edition Shadowrun is a perfect example of this. The game is endlessly derided in forums as “broken” in a variety of ways. But based on ICv2 and Roll20 reports, it’s been quite popular for years.

Of course the fact that a game is popular doesn’t mean it’s the best choice for beginners. It’s quite possible that many a would-be gamer has purchased Shadowrun and found it too complex to play. That may explain why the rules-lite Shadowrun: Anarchy was released. But I’d also be willing to bet that a lot of the newcomers who find Shadowrun too complicated are simply doing what we did back in the day — they’re playing the game their own way.

If people have to make adjustments to a game in order to make it work for them, does that make it “broken”? I don’t think so. We all play games that are imperfect, each in its own way, as we continue to look for that mythical unicorn game that suits our needs perfectly without modification. In the mean time, when we critique games, especially ones we’ve read but never played, we should be careful about how we characterize their shortcomings. Promoting great games is more likely to entice newcomers, but endlessly denigrating the flaws of games we don’t like won’t convince those already playing them, nor will it encourage newcomers.

Image Credit

The Humvee photo is modified fromAboard High Mobility Multi-purpose Wheeled Vehicles (HMMWV), US Marine Corps (USMC) members from the Combined Anti-Armor Team (CAAT), Weapons Company, Battalion Landing Team (BLT), 2nd Battalion, 2nd Marines, 24th Marine Expeditionary Unit (MEU), provide security for a convoy through southern Iraq in support of Operation IRAQI FREEDOMwhich is a US DoD image released to the public and available here.

Ω